Steve Woodcock

-

Posts

622 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Shop

Articles

Posts posted by Steve Woodcock

-

-

[quote name='subaudio' timestamp='1502678071' post='3352802']

Steve, thank you so much for all your effort, very kind indeed of you and has surpassed what I could have wished for, I'll study this tomorrow.

Again, huge thanks.

[/quote]

My pleasure, how are you getting on with it? -

TAB is a mechanical instruction rather than a musical one, i.e. 'put your finger here' rather than 'play this note, on this subdivision of this beat, for this duration'. It is a crutch, it may give you a short term gain but reliance on it will ultimately hinder your potential to be a well rounded musician.

As has already been acknowledged, TAB does not contain all the information you need to perform the piece, meaning it needs to be viewed in conjunction with something else - i.e. either a recording or notation - therefore, as a means of communication it is flawed.

Notation enables us to do the following:[list]

[*]Perform a piece of music at sight, accurately and authentically, having never heard it before.

[*]Read and write music intended for other instruments - '3rd fret on the A string' means nothing to a pianist, horn player etc.

[*]Identify the key of the piece and the harmonic movement contained within

[*]Discern the harmonic rhythm of the piece (the rate at which the chords change)

[*]Recognise familiar melodic or rhythmic groupings of notes - the benefit of this is that these groups can be recognised as a 'whole', much like you are recognising the words in this sentence rather than reading each letter separately, and executed promptly from muscle memory

[*]Quickly see the ascending and descending contour of a line, identify where things move by step or by leap etc., spot potentially tricky passages

[*]Easily recognise sequences and other repeating patterns, even if they modulate to another key

[*]Combined with a rudimentary ability to sight sing allows us hear the piece in our head, and therefore learn it away from our instrument

[/list]

By using notation rather than TAB, you are having to think [i]notes[/i] rather than simply positions - this will increase your knowledge of the fingerboard far more as you will make the association of 'this is an A, this is a C#, etc.' each time you play a note. More work in the short term but the rewards will pay dividends.

[quote name='Dad3353' timestamp='1503065984' post='3355481']

Before what is now 'standard' notation, tab (short for tablature...) was the means of communicating for all serious musicians and composers[/quote]

True, this existed for keyboard instruments and lutes in the sixteenth century but it was found to be unsatisfactory and was replaced by notation for good reason; the systems used also differed from country to country.

[quote name='Grassie' timestamp='1503156674' post='3356116']

IMO anyone who thinks that using tab, chord diagrams or any other tool that helps a player learn their instrument is somehow "wrong", belong in the same category as bassists that believe using a pick is also somehow "wrong".

[/quote]

But here's the rub, TAB [i]doesn't[/i] help a player learn their instrument, it merely tells them where and in what order to put their fingers, it doesn't even teach them what the note is. In the same way as being told to move your Pawn from b4 to b5 in chess doesn't teach you anything about how to play the game, nor does painting by numbers teach you how to paint. To be clear, used in conjunction with another source (recording or notation) TAB may help someone learn to play a song, but they are not learning anything about the instrument. -

I've just done a quick transcription of the part for you, it's important to note where the chord tones are so I have highlighted them in red, I have also noted the melodic devices being used:

[attachment=251348:Signs of the Times - Sons of Apollo.png]

So, the first thing of note is the wholetone scale (plus an additional chromatic passing note) that starts from the fifth of the chord on beat 6 of the first bar, this is giving a very 'outside' sound because of the major 7th and minor 2nd intervals.

The next things of note are the two enclosures - these are devices that encircle the target note with notes from above and below and they are typical bebop language. The first features two chromatic notes from a tone above, then a semitone below, then a tone above; the second is encircled by a semi tone below and a semi tone above.

The last thing of note features the major 9th, minor 7th and suspended 4th of the chord approached by a semi tone above - again, typical bebop language. Note that the sequence continues to the E but this has been displaced by an octave. -

[quote name='wateroftyne' timestamp='1502467839' post='3351718']

Yep - it's about 200 pages, of which 150-odd are transcriptions.

[/quote]

They could have saved 75 pages by getting rid of all of the tab

-

Below is an information sheet on intervals that I give to all my new students, it contains all that you need to know:

[url="http://stevewoodcockbass.com/onewebmedia/Basic%20Theory%201.3%20-%20Intervals.pdf"]http://stevewoodcock...20Intervals.pdf[/url]

And here is a video tutorial I made on seventh chords, including a play along exercise to help you learn them:

[media]http://youtu.be/rY4rkG2pX1Q[/media] -

[quote name='Westenra' timestamp='1502210464' post='3350027']

The opening riff is B C E C, I was questioning that natural E as diatonically it doesn't belong so would it be counted as a passing note?

[/quote]

The phrase is actually B, C, [i]Eb[/i], C - the key signature dictates that every E should be played as Eb unless altered by an accidental. -

[quote name='Westenra' timestamp='1502201735' post='3349955']

Just a quickie, maybe it's because I'm looking at it through novice eyes but there is no Eb, it's a natural E. I guess this is another chromatic note?

[/quote]

The Eb is noted in the key signature (as are Bb and Ab). -

The B natural is simply a chromatic approach note to the C.

In order to analyse these things you need to have an understanding of the underlying harmony so I have posted the leadsheet for Cannonball below.

The phrase the OP is querying occurs in bar 6, the chord here is an Ab major chord in 2nd inversion (i.e. the fifth of the chord, the Eb, is played as the lowest note). An Ab major chord consists of the notes Ab, C and Eb so we can see that Jaco plays a chromatic approach note ([i]B[/i]) to the major 3rd of the chord ([i]C[/i]), then the perfect 5th of the chord ([i]Eb[/i]), then another major 3rd ([i]C[/i]) an octave higher than the first. This major 3rd then becomes the major 13th of the following chord in the next bar:

Chromatic approach notes embellish and/or 'smooth out' diatonic lines and you will find them in abundance in any bebop solo, walking bass lines - or James Jamerson line! They can approach the target note from below or above, and may even be 'double chromatic' (i.e. two chromatic notes in a row). I would strongly recommend adding them to your arpeggio practice routine to really get a handle on them.-

1

1

-

-

[quote name='keva' timestamp='1495453076' post='3303785']

I understand the theory of modes and scales but really don't know how to actually use them in my playing, e.g. for a given set of chords.

Help and examples very much appreciated please.

[/quote]

Hi Kev,

Here's a quick primer/recap on chord/scale relationships. For the sake of simplicity I'll keep to major harmony in this post as minor harmony can get a little more complex.

Let's take C major, it contains these 7 notes:

C D E F G A B

[u][b]MODES[/b][/u]

We can build a scale (or 'mode') on each one of these notes by continuing the sequence using the same set of notes:

I) C D E F G A B = C ionian (or major)

II) D E F G A B C = D dorian

III) E F G A B C D = E phrygian

IV) F G A B C D E = F lydian

V) G A B C D E F = G mixolydian

VI) A B C D E F G = A aeolian (or natural minor)

VII) B C D E F G A = B locrian

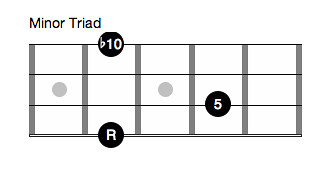

[u][b]TRIADS[/b][/u]

By taking the first, third and fifth notes from these scales we get the following triads:

I) [b]C[/b] [size=3]D[/size] [b]E[/b] [size=3]F[/size] [b]G[/b] [size=3]A B[/size] = C major

II)[b] D[/b] [size=3]E[/size] [b]F[/b] [size=3]G[/size] [b]A[/b] [size=3]B C[/size] = D minor

III)[b] E[/b] [size=3]F[/size] [b]G[/b] [size=3]A[/size] [b]B[/b] [size=3]C D[/size] = E minor

IV)[b] F[/b] [size=3]G[/size] [b]A[/b] [size=3]B[/size] [b]C[/b] [size=3]D E[/size] = F major

V)[b] G[/b] [size=3]A[/size] [b]B[/b] [size=3]C[/size] [b]D[/b] [size=3]E F[/size] = G major

VI)[b] A[/b] [size=3]B[/size] [b]C[/b] [size=3]D[/size] [b]E[/b] [size=3]F G[/size] = A minor

VII)[b] B[/b] [size=3]C[/size] [b]D[/b] [size=3]E[/size] [b]F[/b] [size=3]G A[/size] = B diminished

[b]7TH CHORDS[/b]

By continuing this concept of taking every other note in the sequence we can produce the following 7th chords (this concept can also be extended beyond the octave to produce 9th, 11th and 13th chords):

I) [b]C[/b] [size=3]D[/size] [b]E[/b] [size=3]F[/size] [b]G[/b] [size=3]A[/size] [b]B[/b] = C major 7th

II)[b] D[/b] [size=3]E[/size] [b]F[/b] [size=3]G[/size] [b]A[/b] [size=3]B[/size] [b]C[/b] = D minor 7th

III)[b] E[/b] [size=3]F[/size] [b]G[/b] [size=3]A[/size] [b]B[/b] [size=3]C[/size] [b]D[/b] = E minor 7th

IV)[b] F[/b] [size=3]G[/size] [b]A[/b] [size=3]B[/size] [b]C[/b] [size=3]D[/size] [b]E[/b] = F major 7th

V)[b] G[/b] [size=3]A[/size] [b]B[/b] [size=3]C[/size] [b]D[/b] [size=3]E[/size] [b]F[/b] = G dominant 7th

VI)[b] A[/b] [size=3]B[/size] [b]C[/b] [size=3]D[/size] [b]E[/b] [size=3]F[/size] [b]G[/b] = A minor 7th

VII) [b]B[/b] [size=3]C[/size] [b]D[/b] [size=3]E[/size] [b]F[/b] [size=3]G[/size] [b]A[/b] = B half-diminished (or minor 7 b5)

So, to summarise we have the following chords contained within a major key:

I) maj7

II) m7

III) m7

IV) maj7

V) 7

VI) m7

VII) m7b5

From the above you should be able to see the following relationships between the chords and modes within a major key:

Imaj7 = ionian

IIm7 = dorian

IIIm7 = phrygian

IVmaj7 = lydian

V7 = mixolydian

VIm7 = aeolian

VIIm7b5 = locrian

Back to our example of C major, a VIm-IIm-V7-I progression in that key would consist of the following chords:

Am / / / Dm / / / G7 / / / C / / /

Giving you the diatonic (i.e. from within the key) scale choices of:

A aeolian / / / D dorian / / / G mixolydian / / / C ionian / / /

As dlloyd and dand666 both point out, the important notes to think of in your lines or solos are the chord tones as these convey the harmony, look at the scale tones in between these as stepping stones. An old teacher of mine had a great analogy comparing chord tones to bases in baseball - if you land on one of these you are 'safe', anywhere in between and you can be caught out!

When you become more comfortable with this concept, and the inherent sound of different scales, you can choose to step 'outside' of the diatonic harmony boundary to create tension or imply a brief movement to another key - a common approach amongst jazzers for example is to play lydian over a Imaj7 chord because of the 'brighter' sounding raised 4th in that scale (the perfect 4th in ionian is often viewed as an 'avoid' note' because it clashes with the major 3rd - try it and see for yourself how it sounds). -

Oye Como Va is a modal tune in A dorian. In a setting like this don't think of the A-7 as being 'chord ii of the key' as clearly it is functioning as the tonic chord here (as your ear is already telling you).

Latin music is characterised by [i]rhythm[/i] rather than a proclivity to any particular scale or chord progression, so as per any other style let the harmony be your guide. Most of this tune consists of just two chords, A-7 and D9, so the obvious 'in' sounding scale choices would be A dorian and D mixolydian respectively. -

[quote name='AdamWoodBass' timestamp='1494856261' post='3299035']

[...] when playing my wrist is almost at a 90 degree angle. This is the most comfortable playing position for me in terms of my left hand (fretting hand) but I get it's a fairly extreme angle for my right hand.

[/quote]

This will be the cause of the problem - you should try to keep both of your hands and forearms in as straight a line as possible, as Ambient says this will require a compromise in strap height until this can be achieved. Have a look at this Gary Willis clip where he demonstrates this issue in detail:

http://youtu.be/oRrmxH1wVlE?t=2m12s -

[quote name='jrixn1' timestamp='1494531788' post='3296828']

Well... isn't this the same notational error which exists for all transposing instruments?

A trumpeter who thinks they are playing "B" is actually playing an A.

An alto saxophonist who is playing "their D" is actually playing an F.

Etc.

[/quote]

Oranges and apples but OK yes, for instruments such as trumpet and saxophone the written note [i]does[/i] equate to a fingering rather than the sounded note - as you probably know this is so that a player does not have to learn a different set of fingerings for a [i]different sized version[/i] of that same instrument. When discussing these instruments it is important to distinguish between the written note and the sounded note so as to avoid possible confusion, therefore the sounded note is referred to as the 'concert' pitch: i.e. in your example of the alto sax 'written D' is 'concert F'.

Guitars and basses are also transposing instruments but for a different reason to the above: it is simply to avoid the use of many ledger lines as both guitar and bass sound an octave lower than they are written. Unlike brass and woodwind instruments, whose tuning is dictated by the physical attributes of the instrument itself, stringed instruments can accommodate a wide variety of different tunings - enabling a vast catalogue of works to be composed using altered tunings, open tunings, drop tunings etc., if each of these options required a specially transposed score it would be ridiculous; to us string players a D is a D.

[quote name='Muppet' timestamp='1494532939' post='3296841']

You completely miss my point (assuming it is my post you are referring to). In a band context, as long as all instruments have the same understanding of what a note at a particular point on the fretboard is supposed to represent, then you can call it Ethel for all I care, regardless if it's detuned or not. In the case of the OP they are playing the same note, but calling different things because they are in different tunings...

[/quote]

Actually I was answering the OP, I hadn't read your post. The reason note names and other musical terms exist is simply to explain or communicate information to another person, either through written or spoken means. If everyone in your band agrees that you shall all refer to a particular note as Ethel then that serves that purpose, however there will then be a problem if you want to communicate anything about this note to anyone else outside of the members of your band as everyone else will know that note by another name. -

Mr. Brightside is in the key of Db major (key signature of 5 flats).

A note is named [i]according to its pitch[/i], not its position on a fretboard. I've seen a lot of guitar transcriptions over the years - professionally published ones - that will continue to notate say, a note played at the fifth fret on the A string, as a D regardless of the fact the string is actually detuned to say Ab and so this is wrong, it infuriates me and seems unique to guitar/bass transcriptions usually accompanied by tab. -

[quote name='dlloyd' timestamp='1493237165' post='3286862']

That's what I thought too. However John Fould's World Requiem ([url="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_World_Requiem"]https://en.wikipedia...A_World_Requiem[/url]) apparently has a section written in G# major with the double sharp in the key signature. I have never seen the score.

Edit: And here's one in the key of Fb: [url="http://www.enspub.com/pages/sku93503.htm"]http://www.enspub.co...es/sku93503.htm[/url]

[/quote]

I can't find a copy of World Requiem however I have just found the Ewald score - this is the first score in over 20 years of study where I have seen this written! I still maintain this is highly unusual as there is no reference of such practice in Gardner Read's bible on score writing, [i]Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice [/i](Gollancz, 1974); the only mention I could find was from composer Paul Hindemith, who also denounces their usage:

[indent=1]But in practice, while keys containing more than 7 sharps or flats are occasionally used (as a result of modulations in the course of simpler keys), they are never indicated in signatures.[/indent]

[indent=16][i]Elementary Training for Musicians ([/i]Schott, 1949)[/indent]

Fascinating stuff. -

[quote name='dlloyd' timestamp='1492887868' post='3283969']

There are real pieces of music that are written in keys that fall outside of the limitations you're claiming, but sure, they are few and far between.

It's important to understand that G# is not the same as Ab in use, even if they sound exactly the same on a fixed pitch instrument. There are solid reasons why a composer would use G# major rather than Ab major, for example a modulation from C# major to G# major is far easier for orchestral instrumentalists to deal with than rewriting everything after the key change to Ab major.

[/quote]

Not my limitations, rather those of traditional music notation practices.

You are correct that a modulation to the dominant of C# major would be written in G# major rather than Ab major as to avoid mixing numerous sharps and flats, however my point was that a [i]key signature[/i] with a double accidental is never used and is therefore a theoretical concept. -

I have studied music/bass playing both academically and privately and can honestly say that I learned far more from my private tutors than on my degree course.

As a tutor myself it frustrates me to read the stories on here of bad teachers but sadly there are people purporting to be instrument tutors who simply lack the knowledge, experience and necessary personal skills to actually [i]teach, [/i]unfortunately this may only become apparent after you have a few lessons under your belt but you have no obligation to stay with someone who isn't teaching you properly - there are many great teachers out there and with the advent of Skype lessons geography is no longer the restriction it once was.

The wealth of learning material available to us now, be it in print or online, is overwhelming and I personally would find it incredibly difficult to focus and forge a path of study - and more crucially [i]stick to it - [/i]with so many options and opinions vying for my attention. Therefore, even though we have more information than ever at our fingertips, I believe the guidance of a good tutor to still be the best way to progress. -

[quote name='dlloyd' timestamp='1492858552' post='3283686']

Just to be pedantic, there is no theoretical limit to 7 sharps or flats.

[/quote]

[i]Theoretical [/i]being the key word there, it really is an academic exercise and of no practical use. -

[quote name='Yank' timestamp='1492509157' post='3280749']

In one of my bass books, it has the circle of fifths, but 3 of the twelve it gives both enharmonic equivilents. It lists both B and C flat, D flat and C sharp, and F sharp and G flat. Why these three keys?

[/quote]

Have a look at the diagram below, you will see as you go clockwise (up a perfect fifth) you add one sharp to the key signature - [b]there are only 7 notes in a key therefore the most alterations a key signature can contain is 7[/b]. If you go clockwise around the circle (up a perfect fourth) you add one flat to the key signature - again, the maximum you can have is 7.

[attachment=243332:Circle of Fifths.jpg]

As you have noted three of the keys are enharmonic equivalents of each other:

B (5 sharps) and Cb (7 flats)

F# (6 sharps) and Gb (6 flats)

C# (7 sharps) and Db (5 flats)

F# and Gb both have the same number of alterations (6 each) however B and Cb, and Db and C# have 5 versus 7 alterations - which is easier to read, 5 right? -

My favourite guitarist and a true pioneer of the instrument. Very, very sad that he is no longer with us.

-

[quote name='timmo' timestamp='1492075547' post='3277647']

If I wanted you to play E , 7th fret and C# 9th fret, how would I express that as in intervals? Am I just confusing myself and the issue ?

[/quote]

You would say 'play a [b]minor 3rd below' [/b]as intervals are named from the bottom note up (C# to E = minor 3rd). See the second diagram in my first post as this shows intervals and their inversions. -

[quote name='markstuk' timestamp='1492008032' post='3277144']

Sure, the context of the key defines whether it's a flat or sharp, regardless of whether they're the same note on a keyboard. I was suggesting that this concept is actually quite hard to grasp... My piano teacher got bored of me saying - "but it's the same note"

[/quote]

Haha! Yes, it can be a difficult concept to understand at first but, as with so many other aspects of music theory, there is a very logical reason for it and it does make the communication of ideas much simpler. -

[quote name='markstuk' timestamp='1491999561' post='3277043']

c# and db are the same note

[/quote]

Yes, they are the same but for diatonic notes whether you name it a C# or a Db depends on the key:

A key consists of [b]7 pitches [/b]- the other 5 notes that exist within an octave are non-diatonic notes; a key will contain an A [i]of some kind [/i](be it flat, sharp or natural), a B [i]of some kind[/i], a C [i]of some kind[/i], a D [i]of some kind[/i], an E [i]of some kind[/i], an F [i]of some kind[/i], and a G [i]of some kind. [/i]Therefore, if your key already contains a C then the adjacent note will be a D of some kind. -

[quote name='timmo' timestamp='1491994275' post='3276998']

Am I getting diatonic intervals and chromatic intervals mixed up?

[/quote]

An example of a [i]chromatic[/i] interval would be [b]C[/b] to [b]C#[/b] as this does not occur within any key, whereas [b]C[/b] to [b]Db[/b] (the [i]enharmonic equivalent[/i] of C#) would be a [i]diatonic[/i] interval as this occurs naturally in a number of keys. -

The term [i]interval[/i] describes [b]the distance between two notes[/b], whether played in succession (a [i]melodic[/i] interval) or simultaneously (a [i]harmonic[/i] interval).

The distance between the note E and the C# [u]above[/u], if played within the octave, will always be major 6th [u]regardless of what key it is in[/u]. If the distance is over an octave it is known as a [i]compound[/i] interval - your example of E to C# would be a major 13th.

Here is a diagram showing [i]simple[/i] (occurring within the space of an octave) and compound intervals. To find the simple equivalent of a compound interval, subtract 7 from its number (i.e. 13 - 7 = 6):

[attachment=242865:Simple and Compound Intervals.png]

In your example of E to C#, if you lower the C# by an octave so it is below the E you have [i]inverted[/i] the interval and it becomes a minor 3rd (note that intervals are named from the bottom note up).

[attachment=242866:Inversions.png]

As you can see in the diagram above the original interval and its inversion always add up to 9:

2 + 7 = 9

3 + 6 = 9

4 + 5 = 9

6 + 3 = 9

7 + 2 = 9

8 + 1 = 9

Perfect intervals remain perfect but minor becomes major, major becomes minor, augmented becomes diminished and diminished becomes augmented.

Barring chords

in Theory and Technique

Posted

I presume we are talking about this voicing:

[/url]

[/url]

[url="https://flic.kr/p/XsEc7Y"]

The only notes you need to fret with your first finger are on the E and G string, you don't need to fret the A and D strings so let your finger relax and arch a little (your finger will still be in contact with these strings but it won't be fretting them); if you keep it flat you will certainly experience tension in your hand and wrist.

Try and keep your wrist and forearm straight and do not let your thumb drop too low as this will cause your wrist to bend sharply and will push your hand forward, resulting in the lower part of your first finger losing contact with the G string.